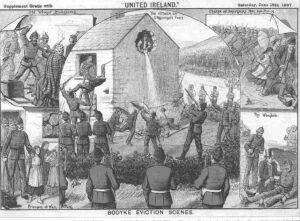

Although the O’Halloran family is not related to our branch of the Kane family in Ireland, yet, we thought their story is important because it gives the sad details about the evictions of poor Irish tenant families from their homes throughout Irish history by their landlords.

John O’Halloran and his family were evicted for failure to pay rent on their tenant home, which they built themselves, and their tenant farm on June 10, 1887 in Lisbarreen, near Bodyke, County Clare, Ireland, which was part of the estate of Col. John O’Callaghan. Their eviction was among many other evictions performed in June 1887 by the orders of Col. John O’Callaghan, the landlord. These evictions of June 1887, from the lands of Col. John O’Callaghan, are commonly referred to as the “Bodyke Evictions”. Many of the tenants defended their homes against these evictions, among which was the family of John O’Halloran. Listed members of the resisting John O’Halloran family was his wife, Harriet, daughters Anne, Honoria and Sarah O’Halloran, and sons Frank and Patrick O’Halloran.

The John O’Halloran family tenant home was so well prepared against the expected eviction that it was referred to as “O’Halloran’s Fort”.

The following story of the John O’Halloran family eviction on June 10, 1887 is from the account of the son, Frank O’Halloran, as listed in The Irish Times newspaper issue of June 15, 1887, and also on file at the Clare County Library, Ennis, County Clare, Ireland.

The Bodyke Evictions: The Evictions

Frank O’Halloran’s Account of his Family’s Eviction

The Irish Times, 15 June 1887

This holding has been handed down to us from generations; it consisted of between 17 and 18 Irish acres, and the rent was, I believe, in my grandfather’s time as low as £13-10s. During my father’s time the rent was increased to £22-10s., or £23-1s., to £31, and it was subsequently reduced in Court to £22-10s. as first-term judicial rent. We did a lot of improvements there. We built the house ourselves — a two-storey slated house, and, with our own labour, it cost us £220, and had almost built an out-house at a considerable cost also. As for the land, no one could work harder than we did to improve it.

When asked if his land was good and if he was able to make a profit, he said that most of the money was got from well-to-do brothers in Sydney and some from the Board of Works. ‘In consequence of this, we considered that we should be well treated, and, when the time for eviction came, we were firmly resolved to defend the house with our lives. Our family consisted of the father and mother, Honoria, Annie, Sarah (Sisters), and Patrick and myself. For weeks before we were making preparations for the siege. We blocked up the doors with formidable logs of trees, and treated the windows in like manner. We also blocked the door which connected the two parts of the ground floor so as to make the progress of the evictors still more difficult when they got in. We were sure they would attack a certain corner of the house, and inside this we heaped up a large quantity of earth and scraws and stones.

We used then to have to get in and out of the house through an upper window by means of a plank, and, or course, we took off the boards of the first floor in order that we could scald the bailiffs when they came in.

On the morning of the eviction we were up at the break of day and laid our plans, each to defend a certain point and none to waiver, whatever might come. We boiled plenty of water and meal, and, when all was ready, we kept a look-out for the bailiffs and the rest of them. At this time I was only home a few months from America, and during my absence, I may add, I did not learn to love Irish landlordism or English rule.

We had not long to wait, as the attacking party appeared over the hill at about half past ten o’clock, and pretty formidable they looked too — police, soldiers, bailiffs, and all followed by a large crowd of tenants. We had two portholes broken out commanding the eastern rear corner, and had plenty of pitchforks and poles to meet the rifles and the bayonets when they would attempt to scale the windows. Mr. Davitt, however, came up and deprived us of the pitchforks. I guess he thought there would be blood spilt if they were there. When the bailiffs approached with picks and axes we waited until they would come near enough for the hot fluid to scald them. The police shouted to us to go in from the portholes or that they would shoot, but we took no notice of them.

I remember that, as they raised their rifles, the thought struck me that it was a queer country where the sons of people were amongst the greatest enemies the people had.

The police were not more than 25 feet away, but they did not fire. The bailiffs attacked the corner, and the sisters threw cans of boiling water on top of them, making them speedily retire, while the girls stood waiting with more water ready to fire, but they took no notice of them either. The crowd outside became terribly excited, as they saw by this that we meant no surrender in earnest. I had a long pole defending the corner, and I found that I could not use it effectively from the porthole which I was at, as I was a left-handed man; so I got an iron bar and broke a hole through the roof, a shower of slates falling on the emergency men outside. Then I got water and took off the slates, which I fired at them, but I don’t think any took affect but, anyway, we had the satisfaction of seeing that we made it impossible for them to continue at the corner. For about three-quarters of an hour the struggle continued, and finally, the defeated emergency men gave up, some of them well scalded. Then they went to the end of the house and the police got scaling ladders to get through the window on the second storey, so I exchanged places with my brother and went to the porthole at the gable-end, which he had been defending up to this.

At this time some unfortunate delay occurred about handing up the water. My brother went to see what was wrong, and while he was so engaged a policeman entered through the window. He was met by Honoria who caught a grasp of his sword-bayonet. He was just bent down in the act of jerking it from her when I saw him. I knew that if he gave the pull he would have cut her fingers off and ruin her hands. There was not a moment to spare. I jumped off the platform and struck him with my clenched fist under the chin and sent him sprawling to the other end of the room. My sister was then in full possession of a rifle, bayonet and all, and sure she did use it. She rushed to the window and scattered the police outside right and left, and cleared the ladder outside, which was crowded. All this happened in a few seconds. My brother had now returned with the water, and I went to Honoria’s assistance. I got a big pole: there was a policeman at the top of the ladder; I put it to his chest, pushed him into an upright position. The policeman behind him pressed him on, while the crowd yelled, wild with delight. I shoved harder and he fell to the ground, amidst deafening cheers and shouts. Others pressed on, to meet the same fate. Now we thought it was high time to evict the policeman we had inside. We got him near the window to throw him out. The police outside rammed their bayonets and wounded us several times, so we had to throw him back again instead of throwing him out. The fight now began properly. We attacked them with all our might and so fierce was the struggle that we smashed a sword-bayonet and injured several of those outside. Eventually we cleared the window again and victory was hailed with thunders of applause outside. The forces outside were dismayed, as if they did not know what to do next.

We thought that the little respite we got could not be made better use of than by ejecting the policeman who still remained inside, so we caught him again.

Out he would have gone at the moment for certain, but Father Hannon was at the top of the ladder. He put up his hands and said: ‘Don’t throw him out, Frank.’ The good priest intervened because he knew that the police would fire the next time.

Well, anyway, his word was law with the whole of us, and little wonder; so I promised him I would do nothing and let him go. The police then rushed in after Father Hannon, and Father Hannon held me as if in a vice. I never felt such a grip before or since. A great big coward of a policeman struck my mother and handled her brutally. ‘Father Hannon’ said I, ‘are you going to hold me while they choke my mother?’ He let me go. I made a spring forward and struck the policeman a blow of my clenched fist, which quietened him anyway.

The house then became full of police, and several of them grappled me. I made no further struggle; I knew that it was useless, and felt satisfied that we had done all in our power. We were all taken into custody to be sent to jail, and Mr. Davitt and Father Hannon got permission for the former to accompany the girls to jail. In a moment or so we were on the car ready to start, when the girls were released, to be prosecuted in the ordinary way. They brought my mother and myself to Limerick Jail, where we were kept until they brought us up for trial. All the tenants took forcible possession immediately, and they remained there until a settlement was come to the following February.

The O’Halloran family were tried and sentenced on June 18, 1887 in Ennis, County Clare, Ireland. Here are the trial results:

Harriet O’Halloran – mother: Freed

Ann O’Halloran – daughter: guilty assault, one month hard labor

Honoria O’Halloran – daughter: guilty assault, one month hard labor

Sarah O’Halloran – daughter: Freed

Frank O’Halloran – son: guilty assault, three months hard labor

Patrick O’Halloran – son: guilty assault, three months hard labor

Frank O’Halloran had been living in the United States prior to the Bodyke Evictions of June 1887. Frank O’Halloran had sailed back to Ireland from Boston, Massachusetts, landing at Queenstown, now known as Cobh, County Cork, Ireland in December 1886.